Negative interest rates have been observed many times in various markets, but over the past few years, have occurred more often than can be explained by a mere anomaly. We have no problem imagining why a government or company would want to issue bonds at a negative interest rate, but why on earth would anyone invest their money by purchasing a bond with a negative interest rate?

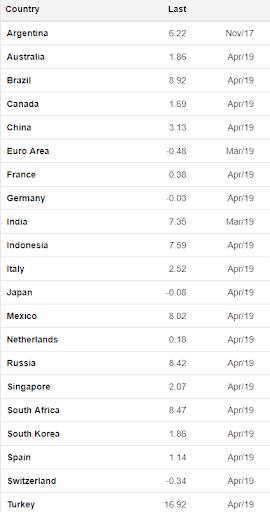

Let’s illustrate what we mean by a bond with a negative interest rate. Unlike a normal bond that is purchased by an investor where the issuer pays the holder interest and principal at maturity (so that principal and interest together equal more than the purchase price), a bond with a negative yield is purchased at a market price that is greater than the sum of future interest and principal payments. Therefore, the investor has a negative rate of return, or a “negative interest rate”. At the time of writing this article, several major developed countries had negative 10-year government interest rates, as depicted in the table of 10-year government interest rates below (Note the Euro Area, Germany, Japan and Switzerland):

Reasons for Negative Interest Rates

First, in the midst of a stagnant or recessionary economy, a country’s government or central bank will likely try to stimulate economic growth through fiscal or monetary policy. A commonly used fiscal strategy is to spend money on infrastructure or other projects to help jumpstart economic activity. Monetary policy can stimulate economic growth by loosening rules and restrictive guidelines to encourage banks to lend for economic development, or by lowering interest rates. Lower interest rates will stimulate borrowing by both businesses and consumers, which in turn is spent on goods and services, thereby stimulating the economy.

Negative interest rates represent the extreme case of lowering interest rates. In Europe, many large institutional investors effectively place excess funds with the banking system, which in turn places funds with the European Central Bank (ECB). The process by which this stimulates the economy is described in the following article from 2016 when the ECB was seeking to stimulate the economy.

“The European Central Bank cut its deposit rate below zero for the first time in 2014. This is the amount commercial banks are paid (or rather, they now pay) on money they leave overnight at the central bank.

Banks have passed this cost on to customers, particularly companies and pension funds with large account balances. In March, the ECB cut the deposit rate even lower, to minus 0.4 per cent.

The cost of leaving their cash on deposit with a bank has led companies and investors to seek out other safe assets. Bonds with negative yields become attractive, so long as these yields are less punitive than those for keeping cash in the bank.

Short-dated investment grade corporate bonds, while still offering negative yields, pay more than cash (and government bonds) as well as being relatively safe.” – “Negative-yielding bonds: Why buy them? Why sell them?” Financial Times, Gavin Jackson, September 7, 2016

The 2016 article coincided with two European corporate bond issues with negative yields in an aggregate amount of €1.5 billion.

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/germany/government-bond-yield

Shifting to “Better” Options

“A report Friday showed factory output in the eurozone fell in March at the fastest pace in nearly six years, while a gauge of U.S. manufacturing activity slipped to its lowest level in nearly two years. The data sent bond prices rising and yields sliding, with the German 10-year bond yield dropping below zero for the first time since 2016 and the yield on the 10-year Treasury note falling to 2.459%, the lowest since January 2018.” – Stocks, Bond Yields Fall Amid Anxiety Over World Economy, WSJ, March 22, 2019

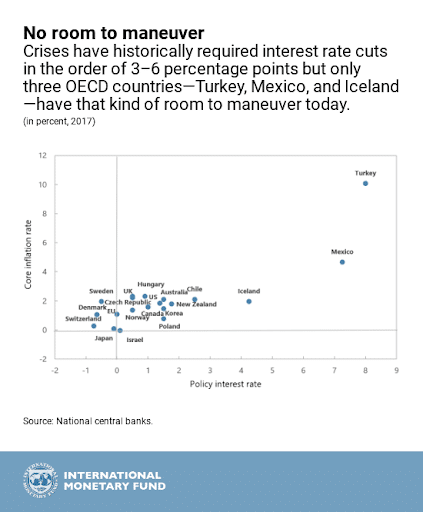

You might be thinking at this point that in order to avoid negative interest rates, we could just hold cash. This of course has limitations as to how much cash you can safely stash in your safety deposit box or wherever. In addition to this practical limitation to storing cash, a recent article published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) observed that historically it takes an interest rate drop of about 3-6% to blunt a severe recession, and only a few countries at present have sufficient room to cut interest rates that far without going negative.

Source: https://blogs.imf.org/2019/02/05/cashing-in-how-to-make-negative-interest-rates-work/

For now, it looks like negative interest rates will remain part of the financial landscape.