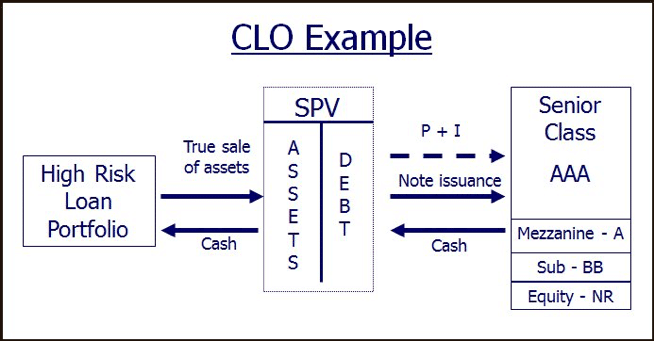

Collateralized loan obligations (“CLOs”) are structured financial transactions where certain types of loans, usually highly leveraged syndicated commercial credits, are pooled together and transferred to a trust entity called a special purpose vehicle (“SPV”). The commercial credits are usually loans issued by financial institutions that are funding high-risk ventures such as leveraged buyouts. The SPV then issues debt to investors to fund the purchase of these loans, and the principal and interest payments that are generated by the loans are paid to investors over time:

CLOs are essentially a type of collateralized debt obligation (“CDO”), and the debt that is issued by the SPV is divided into different classes (sometimes called “credit tranches”). The classes of debt are distinguished by the degree of seniority that an investor in that class has relative to other investors. The most senior class is protected from losses by the more junior (or “subordinated”) classes in that losses on the underlying loan assets are borne by the more junior classes first. The more senior classes are only exposed to losses of principle when the more junior classes have been wiped out by defaults on the underlying assets. Equity investors in the SPV bear the first loss position and receive any residual value after all other investors have been paid.

Parties Involved in a CLO

There are several parties involved in a CLO deal. These include:

- The trustee—oversees compliance of the structure on behalf of the investors.

- The servicer—services the assets (e.g. collecting and disbursing P & I payments).

- The special servicer—advances payments to investors in the event of default but before any recoveries or credit enhancement proceeds, have been collected.

- The asset manager—responsible for managing the assets in the trust.

- The guarantor—guarantees the performance of the trust in the event that collateral loans default.

- The rating agency—provides the credit rating for a fee.

The loans within a CLO are managed by the asset manager, who is essentially acting as an active “portfolio manager” over the life of the transaction. This responsibility includes identifying appropriate assets to be purchased, selling assets that are underperforming, ensuring that cash balances are fully invested, and utilizing tools such as derivatives to hedge undesirable risks. In many ways the financial success (or failure) of a CLO is driven largely by the asset manager. Investors in CLOs should carefully evaluate the previous experience and track record of the asset managers in any deals that they are considering.

CLO Stages of Development

CLOs generally have four different phases or periods:

- Pre-issuance – the asset manager identifies loans appropriate for the structure and arranges warehouse bank financing to begin initial purchase of assets before SPV is established.

- Ramp-up period (approximately six months to one year) – the SPV is established, the asset manager identifies additional assets for the deal, and the cash proceeds of the debt issuance are used to purchase these assets.

- Revolving period (approximately one to five years) -principal proceeds are not paid to investors but rather re-invested in appropriate loans by the asset manager

- Amortization period (approximately five years to final payoff) – principal and interest are paid out to investors according to a pre-determined methodology until the deal is entirely paid off (through asset amortization, early amortization triggers, or embedded call features)

The CLO Market: From 1.0 to 2.0

The first CLO deals were issued in significant volumes in the late 1990s and were targeted at investors desiring to get indirect exposure to the attractive yields and favorable delinquency/default experience associated with leveraged syndicated loans, but who could not economically enter that market directly. CLOs became more and more attractive to institutional investors throughout the 2000’s as a function of the historically low yields available from other traditional fixed income investments during that period. Default rates were also relatively low, especially for the most senior classes. Synthetic CLO structures, where the underlying assets were not loans but credit default swaps (“CDS”) issued on commercial credits, were also popular due to lower initial investment capital requirements and higher leverage. Issuance volumes reached almost $100 billion/year in 20061, the peak of the “CLO 1.0” market.

The market for CLOs, as for most structured financial instruments, began to deteriorate in late 2008 with the advent of the Credit Crisis. Default rates on leveraged loans escalated to about 10% in 20092, resulting in poor performance for many CLO issues and classes. It should be noted, however, that during the Crisis no AAA-rated CLO class ever experienced a default.

Issuance of new CLO structures began again in earnest in late 2010/early 2011. The new issuances generally had much more credit enhancement for the senior classes (30-35% subordination/credit enhancement as opposed to 20-25% pre-Crisis), and there is generally more equity relative to the debt classes, which results in less leverage (and less risk) overall. The vintages of new issues from 2010 through 2013 are usually referred to as “CLO 2.0” deals, and year to date (through August 2013) there have been $57.7 billion in new issues3, an indication of the increased popularity of these structures. There have been no issuances of synthetic CLOs post-Crisis given the relatively lower appetite for risk that investors have after experiencing significant losses in 2008-2009 in both traditional and synthetic structures.

Impact of Dodd-Frank Legislation

Section 941 of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 (DFA) was intended to align the interests of securitization issuers with those of investors by requiring securitizers to retain some of the credit risk in the assets they securitize (“skin in the game”). This initially caused significant concern because CLOs are critical to the U.S. economy: syndicated loans provide $2.5 trillion of financing to U.S. companies4 and CLO managers are major purchasers in the syndicated loan market, providing liquidity and demand for leveraged commercial loans. The risk retention requirements of the DFA could potentially make CLOs less economically viable, reducing demand for leveraged loans and inhibiting macro-economic growth.

On August 28, 2013, Federal banking and securities regulators jointly issued a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPR) which introduced new potential methods for addressing the risk retention requirements mandated by the DFA. The NPR includes an alternative approach for “open market” CLOs which would allow lead arrangers or syndicators of loans purchased by CLO managers to fulfill the risk retention requirement instead of the CLO managers themselves. An “open market” CLO is limited to purchasing only senior, secured syndicated loans acquired directly from sellers like arrangers or syndicators. For CLOs not meeting the definition of an open market CLO (such as synthetic CLOs), the manager would be required to fulfill the risk retention requirement themselves, which would represent a significant economic burden.

Public comments on the NPR are due by October 30, 2013. There will be significant uncertainty in CLO markets until final rules are adopted, which is currently expected to occur sometime in 2014.

CLO Benefits

CLOs offer attractive risk-adjusted returns to investors given the relatively high yields associated with the underlying collateral (leveraged loans), while at the same time offering investors the ability to select the relative degree of credit exposure they wish to take. Banks and insurance companies are attracted to the most senior (AAA and AA-rated) classes, while pension fund and mutual fund managers find more subordinated (but usually still investment grade) classes appealing. Hedge funds and other investors with a high appetite for risk frequently take positions in the most subordinated (BB and lower rated) and equity (non-rated) classes given their potentially high returns.

These instruments are most frequently floating rate assets with coupons tied to three-month LIBOR, providing protection against a much anticipated increase in the overall level of rates in the likely event that the Federal Reserve begins to taper its purchases of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities under the Quantitative Easing program.

CLO Risks

As with other structured financial instruments, CLOs expose investors to a myriad of risks, including:

- Asset manager risk (experience, initial and ongoing asset selection/de-selection)

- Default of underlying loan collateral

- Borrowing commercial entity unwilling or unable to repay principal and/or interest

- Erosion of subordinated credit enhancement over time

- Default of servicer/special servicer

- Market risk

- Liquidity risk

- Valuation risk

Investors should also be aware of the significant increase in leveraged loans appearing in new issues that are “covenant lite.” These credits have relaxed underwriting standards that do not require certain protections to the lender such as restrictions on dividends or merger activity until all debt service has been made. An increase in “covenant lite” loans generally indicates an over-heated lending market where high quality borrowers are scarce and can dictate more favorable credit terms to lenders.

It should be noted that borrowers obtaining “covenant-lite” loans are generally higher quality and more desirable credits. This is because only high quality borrowers have the ability to negotiate these more favorable terms. An increase in “covenant lite” loans within a CLO structure is therefore not necessarily a negative sign. However, the prospectus for the deal should clearly indicate a limit on the percentage of these types of loans within the overall deal structure. Investors should carefully monitor servicer/trustee remittance reports which indicate the concentration of these assets as a percentage of total trust assets.

Notes:

1) Standard and Poor’s Leveraged Commentary & Data (LCD) 2009

2) JP Morgan Global ABS/CDO – Weekly Market Snapshot, Aug 2, 2013

3) Goldman Sachs Weekly CLO Report (Bloomberg) Aug 2013

4) Shared National Credit Review, August 2011 (available at: http://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2011/2011-112a.pdf)

About the author

He is also the President and CEO of Strategic Financial Solutions, Inc., a financial services consultancy specializing in risk management consulting and training for institutions managing market, credit, operational, and other risks. He is a consultant and instructor for the Investment Training and Consulting Institute, Inc. and a Certified Investments and Derivatives Auditor (CIDA). He is also an instructor for many other organizations and industry groups including the FFIEC, the Federal Reserve System, the FDIC, the BAI, the IIA, and the Global Financial Markets Institute.

Rob started his career in 1986 with the Federal Reserve System as an economist in the Research Division and later became a commercial banking and capital markets specialist in Bank Supervision and Regulation. Over his 12 years there, he analyzed the strategies and exposures of on- and off-balance sheet positions, investments, and trading activities of banks, and assessed the adequacy and effectiveness of risk management and recommended strategies to senior management to improve risk monitoring, increase profitability and to reduce the likelihood of failure. Rob chaired a system-wide committee to design, develop and deliver capital markets training to examiners as well as domestic and international financial institutions.

From 1998 to 2000, Rob was a Senior Manager in the Financial Services Industry Group for Accenture, Ltd. where he headed a joint task force responsible for defining and implementing a post-merger organizational structure for First Union’s Brokerage Division’s IT department.

Rob, a charter holder of the Bank Administration Institute’s Certified Risk Professional (CRP) designation and ITCI Certified Investments and Derivatives Auditor (CIDA), has delivered capital markets and risk management seminars to financial institutions across the U.S. as well as in numerous countries in LATAM, Asia Pacific, and Europe.

Copyright © 2014 by Global Financial Markets Institute, Inc.

PO Box 388

Jericho, NY 11753-0388

+1 516 935 0923

www.GFMI.com

Download article